|

May 19, 1999

Internet Fuels Revival of Centralized 'Big Iron' Computing

By STEVE LOHR with JOHN MARKOFF

CHAUMBURG, Ill. -- As Walt Grom tours his domain -- row upon row of hulking black computers -- he speaks of the importance of "fundamental engineering disciplines" and "brute force experience." The vast room is spotless, brightly lit and chilled by air conditioning, an austere interior designed for the care and feeding of big computers.

The huge datacenter, run by IBM, is one of the engine rooms of the Internet, powering the World Wide Web sites and electronic commerce operations of some 400 companies and organizations including BankAmerica, Macy's, Goodyear and the National Hockey League.

Such computer centers, known as server farms, are the unglamorous side of the Internet revolution -- a world apart from the young, urban culture of Web design artists with their tattoos and earrings. Here, a no-nonsense style prevails, and the hallways tend to be populated by big, beefy men with beepers.

Carol Powers for The New York Times

At America Online's Dulles Technology Center employees manage a huge network of servers.

"We're happy to do the plumbing," said Grom, who runs IBM's server farm in Schaumburg.

Internet datacenters are sprouting up across the country in a sure sign of the trend toward once again housing information and computer power centrally -- a seeming reversal of the last two decades of computing.

The personal computer has defined the industry's recent history and how computers were used. As personal computers spread rapidly in the early 1980s, they were seen as engines of individual empowerment and decentralization of information. Millions of islands of information were suddenly stored on desktop machines -- knowledge residing in the spreadsheet, word processing and database programs of individuals. It was a technical and social repudiation of the previous three decades, dominated by mainframes and minicomputers, a computing formula based on "big iron" machines that held all the information.

But in an odd alliance, the Internet -- hailed as the technology behind a new economics, tearing down old hierarchies and flattening corporate organizations -- is fueling a recentralization of information and a revival of big iron computing.

The Internet holds the promise of anytime, anywhere access to information and entertainment delivered over powerful networks to an array of information appliances like handheld devices, cell phones with screens and television set-top boxes, not just personal computers.

That makes the present round of information centralization very different from the old days. The glass-house datacenters of the 1960s were controlling gatekeepers, with information rationed from the center. Today's modern server farms, by contrast, are powerful nodes on the Internet, making information more readily available to individuals.

There are, to be sure, privacy concerns raised by the prospect of creating increasingly large digital storehouses of personal information. Those concerns, technology experts say, require clear-cut corporate and public policies to protect privacy as collecting, storing and distributing information becomes easier and cheaper in a digital economy.

Still, even personal computer pioneers generally regard the shift to Internet-based computing as an irreversible step toward efficiency rather than a retreat from the information democracy they sought to foster.

"People want to own their own information but they don't want to maintain it, and that is driving the shift toward centralization," said Adele Goldberg, a member of the team at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in the early 1970s that created the founding concepts of personal computing.

Because of the Internet, companies are starting to embrace centralized computing again for the first time in decades. "A real mind shift is under way in corporate America," Scott Winkler, an analyst at Gartner Group, a research firm, said.

In some ways, corporate America is following the Internet leaders. For behind an America Online or an Amazon.com is a massive arsenal of computing power. America Online Inc. supports its service to more than 16 million subscribers -- with a million people using the system simultaneously on many evenings -- with two vast server farms in Virginia and a third one planned, a $520-million project announced in March. (Such datacenters are known as server farms because they are veritable crop-rows of big computers that send, or serve, data out to users.)

"The good old economics of scale really do apply when it comes to server farms," Marc Andreessen, the chief technology officer of America Online, said.

The new model of computing -- a proliferation of information appliances linked by the Internet to server farms -- has been called the "post-PC era." For the post-PC vision to be fully realized will take years, and billions of dollars of investment to build ultra-fast digital networks, wireless technology and new kinds of handheld and other devices.

And to say that computing appears to be heading toward a post-PC era is not to say the PC will become obsolete anytime soon. Indeed, the PC industry has benefited from the rise of the Internet so far because the PC today is the principal access device to the Net. Desktop alternatives to the PC like the "network computer," or NC, running only a Web browser for tapping into the Internet -- first proposed in 1996 by Lawrence Ellison, chairman of Oracle Corp. -- have not yet slowed PC sales.

But the evolution toward the Internet model, most analysts agree, represents the most significant change in the industry since the PC replaced the mainframe as the center of gravity in computing two decades ago. The shift represents a daunting challenge to the big winners of the PC industry, Microsoft Corp. and Intel Corp., whose software and microchips are the essential technology in most PCs. Their high profit margins are expected to erode as consumers increasingly use simpler, lower-cost devices to tap into the Internet.

Both companies recognize the challenge and are responding. As one step, Intel announced in April that it was planning a big move into Internet services by building and running server farms. The move seems a big departure for Intel, whose microprocessors serve as the electronic brains of most PCs. But Intel sees the server farms as part of its future of moving beyond the personal computer to become a "building-block supplier" to the Internet economy.

"The PC industry is changing drastically," said Andrew Grove, the chairman of Intel, "and when it's over it probably won't even be called the PC industry. It will become the Web infrastructure industry."

Microsoft is preparing for the day when people may keep much of their personal and professional information on large servers with an initiative called Megaserver. The concept is that a person will be able tap into a large central database via the Web to get e-mail, personal schedules, news, weather updates and other information anywhere, anytime.

The Web hosting business is projected to grow from $696 million last year to $10.7 billion in 2002.

Even Microsoft concedes the access device will not always be a PC. "While the PC will stay central, we realize there is demand for computing on non-PC devices," said Steven Ballmer, the Microsoft president.An early test bed for the Megaserver concept is Hotmail, a Web-based e-mail system, which Microsoft bought for an estimated $300 million in January 1998. Since then, the number of users of the free e-mail service has jumped from less than 10 million to 40 million. With Hotmail, a person can retrieve e-mail from anywhere with any PC or other device equipped with a Web browser instead of being required to use a particular machine loaded with one's own e-mail software.

"Hotmail has served as a big wake-up call for us, and we're delighted that we bought it," John Ludwig, a vice president of Microsoft, said.

Hotmail is supported by four large datacenters, and Microsoft is using them as incubators for developing the heavy-duty software needed to run server farms, thus improving the capabilities of Windows NT, the company's most powerful operating system. But Microsoft, Ludwig notes, is also working to improve the software the user sees, making it easier to use.

"There's more software to write than ever before -- that's the good news for us," he observed.

Microsoft added another centralized information service in April when it acquired Jump Networks Inc., a Web-based calendar and datebook system.

Microsoft's move came a few weeks after America Online purchased an Internet calendar service, When Inc., for an estimated $150 million. The start-up, which stores personal scheduling information on a Web site, started its fast-growing service just four months earlier.

Both companies are headed in the same direction, though from different starting points, one a software giant, the other an online service. Clearly, the line between software and services will increasingly blur as the shift to Internet-based computing proceeds.

In an internal memo last fall titled "The Era Ahead," Bill Gates, the Microsoft chairman, pointed to the opportunity as software becomes more a services business. "We get a closer relationship with customers and a predictable revenue model because they pay us a regular fee for the service," he wrote.

But Gates also warned of the rising threat to some Microsoft products likely to come from online services. "A company such as America Online is in competition for all our information-management software, because they can do it through their servers," he observed.

In Silicon Valley, dozens of start-ups have been created as Internet services to centrally handle personal information. The new companies mostly focus on e-mail, calendars and back-up file storage to insure information is not lost when an individual's PC crashes.

"Many of these applications should be moved onto the Internet because it is more reliable, available everywhere and cheaper," said Eric Brewer, a University of California at Berkeley computer scientist who is a co-founder of Inktomi Corp., a Web software company.

Building and running the computing engine rooms behind these Internet services promises to be a good business for years to come. Yet this behind-the-scenes technology business -- like the market for Internet appliances -- will most likely be more diverse and competitive than the bygone mainframe era, whose dominant supplier was IBM, or the current PC era, ruled by Microsoft and Intel.

The start of the trend back to central computing has already been rewarding for the established producers of "big iron" machines like Sun Microsystems Inc., a leader in computers running the powerful Unix operating system, and IBM, whose mainframes have been retooled as Internet servers. The big Unix and mainframe server computers range in price from $100,000 to millions of dollars.

"The big growth for us has been in everything-dot-com -- the revolution in Internet commerce in all its forms," said Edward Zander, the president of Sun.

Indeed, as more and more companies begin to view the Internet not as an experiment but as a technology on which they run their businesses, they need Web sites, e-mail networks and Internet order-processing systems to be up and running around the clock, seven days a week. That kind of reliable, industrial-strength computing is the traditional bailiwick of mainframes and Unix systems.

Still, PC technology is improving steadily and PC servers -- typically using Intel microprocessors and Microsoft's Windows NT software -- are increasingly tackling heavy-duty computing chores. Some heavily trafficked Web sites, handling huge amounts of business, are backed up by server farms using mostly PC technology.

Dell Computer Corp., a direct marketer of PCs, says that sales from its Web site are now running at a pace of $5 billion a year. "Look at our Web site," Michael Dell, the company chairman, said. "It's Dell servers running Windows NT. Yes, we have a way to go at the high end of computing, but don't bet against the PC industry."

Gary Hargreaves does not much care about who supplies the technology. He just wants it to work.

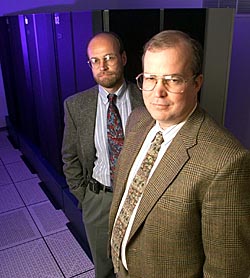

Todd Buchanan for The New York Times

Walter J. Grom, right, is a director at IBM and works with Wiliam Barnett to manage day to day operations of IBM's huge electronic commerce network.

Hargreaves manages an electronic commerce project at Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. -- a company Web site set up to more efficiently distribute and share information with its tire dealers.

The current system, which is gradually being phased out, is costly by any measure -- time, paper or aggravation. Three thick packets of documents are mailed out each week to Goodyear's 2,400 dealers in the United States and Canada. The company's call center in Akron, Ohio, receives 2,500 inquiries a day from the dealers, many of which are merely to obtain routine information on prices and the availability of tires.

All of that kind of information -- along with sales reporting -- is being transferred to the Web site. A third of Goodyear's North American dealers are online and using the Web site, though the rest are joining soon, and Hargreaves is already impressed by the results. The call center is reporting fewer routine calls, he says, and dealers say they are getting more timely information, which helps them sell more tires and improve customer service. The weekly mailings will be stopped at the start of next year.

For all the attention understandably focused on the meteoric rise of online retailers and auctioneers, like Amazon and Ebay, the biggest economic impact of the Internet in the next few years is expected to be inside old-line companies like Goodyear -- boosting productivity by electronically automating back-office transactions.

Though Goodyear has an in-house datacenter, it chose to let outside experts provide the computing power for its Web site -- a role known as hosting -- and run its electronic commerce network. Many companies are making the same choice. That is why the Web hosting business of both established companies like IBM and AT&T, and newcomers like Exodus Communications Inc. and Verio Inc., is projected to grow from $696 million last year to $10.7 billion in 2002, according to International Data Corp., a research firm.

Internet companies like America Online, to be sure, will have their own server farms. But others increasingly view computing as a utility, a service to be purchased like electricity. Indeed, technology historians note that when factories began using electricity in the late 19th century, each had its own power plant. Later, regional utilities were created and sold electric service to the factories.

At Goodyear, Hargreaves seemed to apply the same logic to his company's decision to have its Web site for dealers managed by IBM at its server farm in Schaumburg. "We're in the tire business," he explained. "Why run the digital power plant ourselves?"

Quick News |

Page One Plus

| International |

National/N.Y.

| Business

| Technology |

Science | Sports | Weather | Editorial |

Op-Ed | Arts | Automobiles | Books | Diversions | Job Market |

Real

Estate | Travel

|