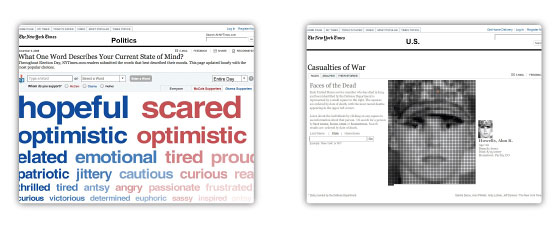

On the day Barack Obama was elected, a strange

new feature appeared on the website of the New York Times. Called

the Word Train, it asked a simple question: What one word describes your

current state of mind? Readers could enter an adjective or select from a

menu of options. They could specify whether they supported McCain or

Obama. Below, the results appeared in six rows of adjectives, scrolling

left to right, coded red or blue, descending in size of font. The larger

the word, the more people felt that way.

All day long, the answers flowed by, a river of emotion—anonymous,

uncheckable, hypnotic. You could click from Obama to McCain and watch the

letters shift gradually from blue to red, the mood changing from giddy,

energized, proud, and overwhelmed to horrified, ambivalent, disgusted, and

numb.

It was a kind of poll. It was a kind of art piece. It was a kind of

journalism, but what kind?

This past year has been catastrophic for the

New York Times. Advertising dropped off a cliff. The stock sank

by 60 percent, and by fall, the paper had been rated a junk investment,

announced plans to mortgage its new building, slashed dividends, and, as

of last week, was printing ads on the front page. So dire had the

situation become, observers began to entertain thoughts about whether the

enterprise might dissolve entirely—Michael Hirschorn just published a

piece in TheAtlantic imagining an end date of (gulp)

May. As this bad news crashed down, the jackals of Times

hatred—right-wing ideologues and new-media hecklers alike—ate it up,

finding confirmation of what they’d said all along: that the paper was a

dinosaur, incapable of change, maddeningly assured as it sank beneath the

weight of its own false authority.

And yet, even as the financial pages wrote the paper’s obit, deep

within that fancy Renzo Piano palace across from the Port Authority,

something hopeful has been going on: a kind of evolution. Each day,

peculiar wings and gills poke up on the Times’ website—video,

audio, “drillable” graphics. Beneath Nicholas Kristof’s op-ed column,

there’s a link to his blog, Twitter feed, Facebook page, and YouTube

videos. Coverage of Gaza features a time line linking to earlier

reporting, video coverage, and an encyclopedic entry on Hamas. Throughout

the election, glittering interactive maps let readers plumb voting

results. There were 360-degree panoramas of the Democratic convention;

audio “back story” with reporters like Adam Nagourney; searchable video of

the debates. It was a radical reinvention of the Times voice,

shattering the omniscient God-tones in which the paper had always grounded

its coverage; the new features tugged the reader closer through comments

and interactivity, rendering the relationship between reporter and

audience more intimate, immediate, exposed.

Despite the swiftness of these changes, certainly compared with other

newspapers’, their significance has been barely noted. That’s the way

change happens on the web: The most startling experiments are absorbed in

a day, then regarded with reflexive complacency. But lift your hands out

of the virtual Palmolive and suddenly you recognize what you’ve been

soaking in: not a cheap imitation of a print newspaper but a vastly

superior version of one. It may be the only happy story in journalism.

I met with members of the teams that created

the Word Train in a glass-walled conference room, appropriate for their

fishbowl profession. There was Gabriel Dance, the multimedia producer, a

talkative 27-year-old with two earrings and a love of The Big

Lebowski. There were Matt Ericson and Steve Duenes from graphics,

deadpan veterans who create the site’s interactive visuals—those pretty

maps that conceal many file cabinets stuffed with data. And there was Aron

Pilhofer, a skeptical career print journalist with “nerd tendencies,” one

of the worried men who helped spearhead this mini-renaissance.

“It was surprisingly easy to make the case,” says Pilhofer, describing

what he calls the “pinch-me meeting” that occurred in August 2007, when

Pilhofer and Ericson sat down with deputy managing editor Jonathan Landman

and Marc Frons, the CTO of Times Digital, to lobby for intervention into

the Times’ online operation—swift investment in experimental

online journalism before it was too late.

“The proposal was to create a newsroom: a group of

developers-slash-journalists, or journalists-slash-developers, who would

work on long-term, medium-term, short-term journalism—everything from

elections to NFL penalties to kind of the stuff you see in the Word

Train.” This team would “cut across all the desks,” providing a corrective

to the maddening old system, in which each innovation required months for

permissions and design. The new system elevated coders into full-fledged

members of the Times—deputized to collaborate with reporters and

editors, not merely to serve their needs.

To Pilhofer’s astonishment, Landman said yes on the spot. A month

later, Pilhofer had his team: the Interactive Newsroom Technologies group,

ten developers overseen by Frons and expected to collaborate with

multimedia (run by Andrew DeVigal) and graphics. That fall, the

Times entered its pricey new building, and online and off-line

finally merged, physically, onto the same floor. Pragmatically, this meant

access to the paper’s reporters, but it was also a key symbolic step,

indicating the dissolution of the traditional condescension the print side

of the paper held toward its virtual sibling.

|

THE WORD

TRAIN (left) This interactive mood database appeared on the

home page of the New York Times on Election

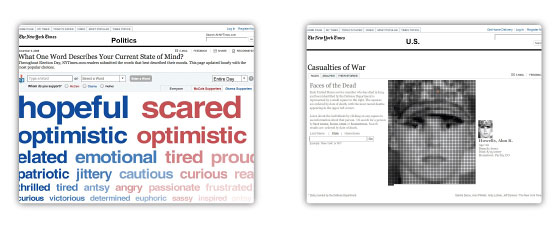

Day. CASUALTIES OF WAR: FACES OF THE DEAD

(right) Merging photography, databases, audio, and

graphics, this project marked the date U.S. military fatalities in

Iraq reached 3,000.

|

It was a particularly gratifying moment for Dance, who had joined the

New York Times at 24, convinced—with the radical innocence of the

cocky Kerouac fan he was—that he was entering a golden age of journalism,

not overseeing its death throes. Dance was uninterested, even when he

graduated from college, in 2004, in the whole “work in Podunk for a small

paper and earn some chops” model. Certain facts about journalism online

struck him as obvious and inevitable: the legitimacy of the first-person,

the immediate, and the anonymous, as well as the notion that sources

should be shared and transparent.

But when Dance was hired by the Times, in 2006, shortly after

completing an experimental-journalism program at the University of North

Carolina, that glimmering Utopia seemed far away. Dance had no boss, no

real department. His cubicle was located eight blocks away from the main

Times Building. “I took the job because they had agreed to embrace

integration,” Dance recalls. “But at first it was difficult, very

difficult—we’d make sure we were in on a meeting, but if we didn’t go up,

that meeting was going on regardless. Nobody was coming over to the

dot-com.”

In the aftermath of the pinch-me meeting, the

group began launching a series of audacious new features. The year before,

they had developed Casualties of War, the website’s first

“database-driven, outward-facing application,” which had debuted on

December 31, 2006, the date U.S. military fatalities in Iraq reached

3,000. The project combined graphics, databases, and audio—but putting it

together was “total torture,” Pilhofer tells me with a laugh, recalling

weeks of scratch-coding. “It feels like dog years since then.”

Casualties of War featured three tabs. On the first, Faces, the reader

confronted one large black-and-white soldier’s face: a raw and isolated

image. A second glance revealed that first image to be made up of smaller

pixels, and when you ran your mouse over the surface, each revealed

another name and date. Click that pixel, and the central photo changed to

the new soldier. A search engine allowed readers to find individuals by

name or hometown. Grim and elegant, it aimed to “show one person, but give

the feeling that they’re one of many,” says Dance.

A second tab, Analysis, contained an enormous cache of data,

graphically displayed: deaths by age, race, branch of service. You could

mouse over a map with deaths by province, or isolate incidents, like the

second invasion of Fallujah. A time line with a movable “scrubber” let

readers compress the scope of information. The final tab, Their Stories,

was frankly narrative, with audio interviews with family and colleagues,

the equivalent of clips from a reporter’s recorder—a different effect than

reading quotes, less curated, more emotional.

Casualties of War won a Malofiej International Infographics Award, and

set the stage for experiments with storytelling in the Times

voice. There were video features of Darfur’s Generation X and of the

“Vows” column; a dizzying tour through the Met’s Greek and Roman

galleries; a partnership with the site Bloggingheads, which streams webcam

discussions among pundits and activists. Some attempts were downright

weird, like the Pogue-o-matic, a hologrammish feature in which an antic

David Pogue analyzed new technology. Others fell flat, like TimesPeople, a

rudimentary social-networking site.

Perhaps most interesting, there were data dumps of documents. As

Guantánamo records emerged, the Times’ website posted the entire

set of legal documentation, affixed to a search engine. Readers could

click on William Glaberson’s reportage, but they could also dive into

original materials, searching for a particular word or prisoner amid

transcripts of legal hearings.

“In the early days, the attitude ranged from a few early adopters to,

at the opposite end, the hostile people,” Jonathan Landman tells me of the

cultural transition at the paper. “Now at the adoption end are a lot of

people—and at the hostility end, almost nobody. Well, so few it’s of no

importance.”

Of course, despite this massive cultural shift, no one had yet figured

out how to, in that hideous term, “monetize” online readers—a massive 20

million unique visitors per month compared with the daily print edition’s

readership of 2.8 million (4.2 million on Sundays). Still, as Landman puts

it with a certain delicacy, “We’re trying very hard to protect it, because

that’s where the action is.”

These experiments were hardly occurring in a

vacuum. The Word Train echoes Twitter’s pithy revelations and also the

magnificent tag-cloud art piece We Feel Fine. For over a decade,

web entrepreneurs have thrown far cheaper spaghetti against the wall,

beginning with Drudge. There’s the Smoking Gun, Wikipedia, and especially

Josh Marshall’s Talking Points Memo—which provides its own daring vision

of what online journalism might be. It has become easy to imagine a future

without a “paper of record,” in which news arrives in many forms: some

authoritative, some fly-by-night, some solo, some collaborative.

Yet there is something exhilarating about watching web innovation

finally explode at the Times, with its KICK ME sign and burden of

authority. Elements like the Word Train appear at first glance quite

un-Timesian, but at second, they provide a philosophical

jolt—what is the Word Train, after all, but a variation on the classic

“streeter,” that roundup of quotes from twenty voters, this time done with

many anonymous thousands? Despite the effectiveness of blogs, the majority

still mainly provide links and commentary. The Times Online suggests what

might happen when technology fuels in-depth reportage—and more radically,

when readers are encouraged to invest their own analytical skills in the

site’s raw resources, when some kid in Kansas finds fresh patterns in an

open electoral database, then posts on his blog with a link back to the

Times, enabling an expansive, self-correcting interpretative

voice.

If there are readers who question these changes, the mood within the

Times suggests that resistance dissolves with surprising

swiftness. “Only history will judge whether we should have made the

real-estate move we made—but that integration, when the web co-located

with the people who made content for the paper, it came at a really

opportune moment,” says David Carr, whose Oscars-season Carpetbagger blog

was one of the earliest genre-breaking experiments at the website. “We

were ready. And it also validated what we had all been thinking, which

was, These guys are Timesmen. They have a different

skill set, but they share objectives, standards. And behind that came lots

of changing metrics on what constitutes success around here.”

Carr is no credulous online utopian. The gorgeous multimedia site he

created to promote his recent memoir sold “no books,” he tells me; he

worries that too much experimentation might overwhelm his readers—and

about how they will pay for it all. Yet creatively, and as a journalist,

he relishes the cultural shift. “This notion of ‘Let’s give it a

whirl’—that’s not how we act in our analog iteration. In our digital

iteration, there’s a willingness to make big bets and shoot them down if

they don’t work. And yet it’s all very deadly serious. Other print

websites can innovate because nobody’s watching. Here, everybody’s

watching.”

There’s another face of innovation at the Times

Building, in a lab on a separate floor: research and development. I spoke

to Nick Bilton, who designs what his website describes, with ominous

confidence, as “technologies that will become commonplace in a

24-to-48-month time frame.”

Bilton’s team works on emerging platforms. Other teams cover analytics

and multivariant testing; everyone seems to have a job title like

“creative technologist,” giving the entire floor a mad-scientist air. Near

Bilton’s desk, a table is littered in Kindles and other experimental

displays for e-ink. There’s also an old-fashioned newspaper kiosk with a

touch screen up top—I tap on it nervously, and options for selecting

articles appear. It’s a joke display, Bilton explains; but then again, he

demonstrates, it actually works. When Bilton swipes his Timeskey

card, the screen pulls up a personalized version of the paper, his

interests highlighted. He clicks a button, opens the kiosk door, and

inside I see an ordinary office printer, which releases a physical

printout with just the articles he wants. As it prints, a second copy is

sent to his phone.

The futuristic kiosk may be a plaything, but it captures the essence of

R&D’s vision, in which the New York Times is less a newspaper

and more an informative virus—hopping from host to host, personalizing

itself to any environment.

Bilton and his colleague Michael Young walk me to a space-age living

room, a holodeck for future media. There’s a sofa, a flat-screen TV, and

four smaller screens. One displays a traffic map, another a pretty avatar

of a newscaster, the third a Twitterlike list of recommendations. There’s

also an ambient green glowing device that measures stock prices, a squat

something called a Chumby, and an “air-mouse.”

As we chatter about the potential for multi-touch walls covered in

physical sensors, Bilton demonstrates his technologies. He slides his

finger across the rainbow-striped, Twitter-ish “Lifestream,” dragging a

stripe off the edge, only to have it pop up on another, larger screen,

then open out into a video of food writer Mark Bittman pouring some milk

into a pitcher. He touches another Lifestream strip—a recommendation from

a friend that he read a certain article—and the software texts the article

to his iPhone.

Bilton praises his bosses, especially Landman, who he feels truly gets

the necessity of investing in these projects. But he also admits to a

distinct generational divide at the paper, describing a trip he took out

to Seattle with Arthur Sulzberger Jr. and other older Times

bosses, on a private plane. “Four of them were reading the paper, folding

it this crazy way, the way people fold it on a subway platform—to show

just one column at a time,” marvels Bilton. “They’d been doing it for 40

years.” I ask him how he reads the paper. “Me, I don’t read the paper

anymore. I read the website. I read the mobile site. When I read the print

paper, I get frustrated—I find I have to sit by the computer and Google

things.”

Half the battle, in Bilton’s experience, is fighting older readers’

nostalgia, which to him is a kind of blindness. “ ‘I like the way

paper feels,’ ” he scoffs. “To the next generation, that doesn’t mean

anything. You know, if we were all reading Kindles, and someone began

raving about this new technology, the ‘book’—here’s something you can’t

share, can’t search, that only holds 500 pages—no one would be

interested.

“Print is just a device. The New York Times is not just a

newspaper, it’s a news organization.” For those who believe these changes

are gimmicks, he has no patience: “This isn’t a storm! This isn’t

something that’s going to pass! It’s the ice age. People aren’t going to

suddenly open their eyes and we’re back in print.”

A few weeks after our first meeting, I join

Dance, Pilhofer, and Duenes for drinks at the Algonquin. In the interim,

the website has fizzed with change. During the Mumbai bombings, the home

page solicited the submissions of strangers; just that morning, the site

launched Times Extra, an alternate home page linking to other news

sources. Intended to make the newspaper open-ended, it just seems busy:

one bit of spaghetti likely to fall off the wall.

As we talk, the generational gulf between the coders becomes

hilariously apparent: “You graduated in 2004?” moans Pilhofer, who didn’t

realize quite how young Dance is. We older folks do our early-technology

rag, trading experiences with basic and Pong, recalling the days when a

newspaper’s website was uploaded from a single hard disk, then back to

college, when publishing involved literal cutting and pasting.

In contrast, when Dance was in high school, he was running a Dave

Matthews music-sharing site and playing Doom with global opponents. But

even more than his seasoned colleagues, Dance is inflamed by his sense

that his employer’s reputation is something embattled, very

vulnerable.

“When I came to the Times, I knew that a large percentage of

the population did not trust where I was going to work. The idea that it’s

all just manipulated by some guy at the top, it really lit my fire: I was

like, ‘These are great, great journalists!’ They’re being slandered by

these people who don’t feel that it’s legitimate work, you know what I

mean?” By exposing their work process online, journalists won’t lose their

validity, in Dance’s view. Instead, they’ll reestablish themselves as

trustworthy curators of data—custodians of the true and the quantitative.

“The Internet provides a way to say, ‘Look, this is real. Real, real,

real.’ ”

It’s a beautiful dream, enough to make one hope that these experiments

will kick-start—unlike so many online renaissances—a sustainable new

model, giving journalism itself an opportunity to spark back to life. What

is a front page, after all, other than an aggregator? Why does an article

read the way it does—lede, nut graf, quotes? If that pyramid structure was

designed for the physical facts of print production, what new structures

will match the new technologies?

There are skills the Times geeks admire that could enlarge the

capacities of journalists: a respect for databases, a sweeping fascination

with the quantitative. (Pilhofer’s background is in quantitative history,

which itself reshaped the romantic landscape of academia.) Also, a

willingness to risk exposure, as well as a curiosity about visual tools

that do not always come naturally to people who identify as writers. In

this new world, reporters reveal their personalities as part of their job,

a loss as well as a gain—many writers went into this business precisely

not to be personalities, to subsume their work into that of a greater

institutional voice.

It is of course impossible to see into the future (despite the

Times’ actually hiring a “futurist,” no longer employed). But

Pilhofer has an application in at the Knight Foundation, a proposal for

which he’s teamed up with the nonprofit newsroom ProPublica, seeking

funding for software called Document Cloud. Like many innovations, it’s

hard to describe until it exists, but from Pilhofer’s account, it would

let news organizations display documents on the web—rich transcripts,

polling, and other research tools—rendering them easily searchable,

commentable, sharable. It could become a journalistic form in itself: the

reporter’s cache, embedded in commentary from every corner.

“One of the New York Times’ roles in this new world is

authority—and that’s probably the rarest commodity on the web,” explains

Pilhofer as the waiter gives us our check. “That’s why in some respects

we’re gung-ho and in other respects very conservative. Everything we do

has to be to New York Times standards. Everything. And people are

crazy about that. And that’s a good thing.”

Over time, Pilhofer adds, this is the role the Times can play:

exciting online readers about the value of reportage, engaging them deeply

in the Times’ specific brand of journalism—perhaps even so much

that they might want to pay for it. If this comes true, it would mean this

terrible year was not for nothing: that someday, this hard era would prove

the turning point for the paper, the year when it didn’t go down, when it

became something better. Pilhofer shrugs and puts his glass back down on

the Algonquin table. “I just hope there’s a business model when we get

there.” |